Professor Trevor Price of the Department of Ecology and Evolution has a new paper out in Evolution. The study explores “how conflicting selection pressures of species recognition and sexual selection are resolved in a genus of Himalayan birds that sing exceptionally similar songs.” Co-authored by retired Indian Forest Service officer Pratap Singh, the paper was highlighted in the journal as an Editor’s Choice selection. Here, Professor Price gives a condensed and lively account of the study.

Human languages rapidly evolve, as we improvise and copy words. Many Americans either complain about or admire an English accent, or sometimes even confuse it with an Australian accent (much to an Englishman’s regret). Nearly half of all bird species also learn and copy; they too are often divided into dialects, with different populations of the same species singing recognizably different songs. It is quite surprising therefore, that three east Himalayan species “have extraordinarily similar vocalizations that can hardly be distinguished [by us], if at all” (quoted from a popular field guide, see footnote 1).

Despite two million years of separation (five orders of magnitude more time than Brits and Americans have occupied different continents), two of these species can’t (or at least don’t) distinguish their songs. Pratap Singh played back songs of Buff-chested babblers (breeding at high elevations) and Rufous-capped babblers (breeding at low elevations) to males of each species (see footnote 2). The birds attack the speaker just as vigorously if the song comes from their own species or the other species. All the evidence is that transmission in the dense undergrowth these species occupy is most efficient using a very simple repeated song. Once an ancestral species had evolved a solution to the transmission problem, any bird singing something different would be less successful at defending territories (and/or attracting mates), leading to extraordinary stasis.

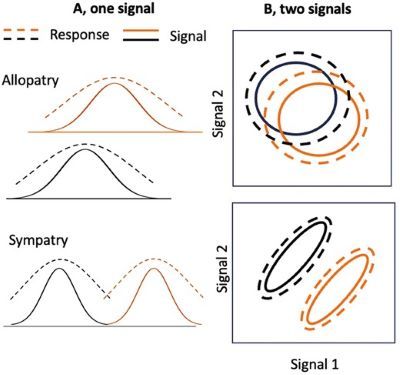

There is, however, another babbler in the middle elevations, also singing a similar song. This creates a problem because it encounters the other species at both the lower and upper parts of its range. If its song were to remain the same, many attacks would be between species: not good for either the singer or the listener. In fact, the golden babbler’s songs differ slightly in syllable structure (i.e. “words”). The songs also differ in frequency, but only where the golden babbler co-occurs with the upper or lower species. We showed experimentally that both syllable structure and frequency are employed by the birds to distinguish each other’s songs, but together these quite subtle differences result in the species ignoring each other, and never attacking the speaker if another species song is played. Presumably we too would rapidly learn to tell Australian and English accents apart, if it meant we avoided attacks.

1 Rasmussen, P. C., and J. C. Anderton. 2005. Birds of South Asia: The Ripley guide. Volume 2: attributes and status. Lynx, Barcelona.

2 Singh, P. and T. D. Price. 2024. Evolution of species recognition when ecology and sexual selection favor signal stasis. Evolution 78: 1647–1660.